Do Crunches and Sit-ups Get A Bad Rap?

2019-04-29

Ah, the fitness landscape in 2019. It isn’t really that things are too different than they have been for years. The difference is that it is so easy to hear people’s opinions so quickly and so loudly, thanks to social media. In fact, one of the easiest things to do to stay relevant in today’s crowded fitness landscape is simply to just say the opposite of what most experts are saying. I love doing this because our blog is a good platform to provide you the science rather than someone wanting to rant on the internet. This is actually important because looking at topics like crunches and sit-ups which are getting a bad name are really debates about people’s health!

This post isn’t about being right and proving others wrong, rather, thinking what is best for those that come to us and entrust us to do what is best by them. In order to appreciate the discussion of crunches and sit-ups we have to know where each party is coming from.

The No Crunches and Sit-ups Side

First off, the science that offers us more about core training than crunches and sit-ups doesn’t actually completely write off these exercises. Well, that isn’t completely true. Before we go down that road, how did we go from crunches and sit-ups being so foundational to our training to the nemesis?

Much of it started with the work with renowned spine expert, Dr. Stuart McGill. Whether you want to agree with everything Dr. McGill says or not, it is hard to deny that he has done more research on the spine than almost anyone else. In his work he came to this conclusion about “flexion based” exercises that both crunches and sit-ups represent.

“Flexion movement of the spine strains the layers of collagen in the spinal discs. When loads on the spine are small, movement is healthy. We often recommend the cat‐camel motion exercise taking the spine through an unloaded range of motion. Thus, there is a time and place for flexion motion. When the spine loads are high in magnitude with repeated flexion motion, the collagen fibers delaminate in a cumulative fashion. Slowly the nucleus of the disc will work through the delaminations and create a disc bulge. The greater the load, and the greater the repetitions, the faster this will occur (Tampier et al, 2007, Veres et al, 2009). Several other events occur depending on the amount of stretch on the spine ligaments at the end‐range of flexion. For example, cytokines linked to acute and chronic inflammation accumulate with repeated full‐flexion motion exposure (D’Ambrosia et al, 2010).”

In other words, doing a lot of spinal flexion (mostly lumbar flexion we are discussing here) the greater POTENTIAL we have in wearing out our spines. We place the spine at greater risk of a host of issues by doing so. Of course, before I can finish this sentence, there are those that will say, “but we are made for flexion”. Well, that’s not wrong and it isn’t right!

Are We Made For Flexion?

There are several points Dr. McGill makes in regard to this comment. The first being that all our spines have differences. Our tolerance to spinal flexion load and/or volume depends upon our structure. So, my question to those that want to do such exercises is, “how are you evaluating people to make sure you are meeting the capacity of their spines?” Usually this is received with crickets.

Another point is flexing the spine loaded or unloaded, high reps, or a few. As Dr. McGill stated in the above quote, doing some unloaded spinal flexion for a few repetitions and the right time of day (avoiding early morning when discs are not as hydrated can be a good idea) can keep a healthy spine. However, this is very different from the argument for crunches and sit-ups.

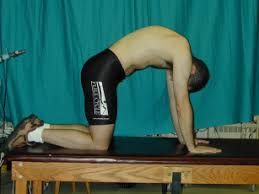

Cat camel exercise is a safe way to train flexion of the spine with minimal risk.

Some will go back to outdated anatomy and say, “isn’t our rectus abdominis (muscle down the center of our trunk we think classically for “six pack”) made for trunk flexion?” Not really and research shows that we may have misunderstood the real purpose of this muscle and more from not thinking how our core works in life. Dr. McGill breaks down why good core function is really important!

“Why is “flexion exercises” such a passionate issue? Core training, training the abdominals, core stiffness and stability are all essential components for pain control, performance enhancement, and injury resilience. But the specific issue here is whether the spine needs flexion movement or flexion moment training. The following section explains the foundation for athletic performance that has 4 components: 1) Proximal stiffness (meaning the lumbar spine and core) enhances distal athleticism and limb speed; 2) A muscular guy wire system is essential for the flexible spine to successfully bear load; 3) Muscular co‐activation creates stiffness to eliminate micro‐movements in the joints that lead to pain and tissue degeneration; 4) Abdominal armor is necessary for some occupational, combative and impact athletes. Logically, we must now discuss the priority for flexion movement or moment.”

You see that the core is not really used to produce force, but rather be a transmission system for the upper and lower body as well as providing a strong platform for the legs and arms to perform. Understanding how the core functions helps us create and focus on better exercises for our core’s performance.

Bird Dogs are one of Dr. McGill’s favorite ways of training the core to function as it is designed in life.

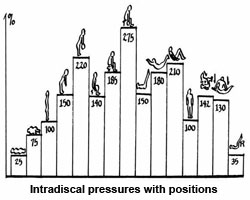

Lastly, why people call sit-ups (more so than crunches as we will explain) as “dangerous”? The most important fact is the force that it creates upon the lumbar spine. Research has shown that traditional sit-ups impose 3,300 N of compression on the spine. Is that good or bad? Well, the National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health has set the action limit of low back compression at 3,300 N because repetition loading above this level is linked with higher injury rates, yet this is imposed on the spine with each repetition of a sit-up. So, while you can survive sit-ups the question is “for how long?”

Stress on the low back (not looking at just shear) during sit-ups is one of the highest activities we can use. The phase of a deadlift is high but that also considers compression as there shouldn’t be actual movement of the lumbar spine.

More advanced forms of core training involve learning how to keep our “plank” as we use more mobile areas of our body like our hips and keep stability through the trunk and pelvis.

The Crunches and Sit-up Group

I think it is obvious which side of this discussion I fall to, but let’s be fair and look at the other side. A common argument is that our spine is made for flexion. Yes, as I discussed it depends on factors like load, number of repetitions, time of day, and even your own genes. We all have a finite number of what Dr. McGill calls “flexion cycles” which he admits varies upon the person. Having high loads, volume, and/or both greatly reduces the number of cycles we have in our lifetime. So, we have to ask if we want to shorten our spine’s lifespan in our training?

Another argument? “I’ve done it for years and never had a problem.” Well, one of my favorite counterarguments is, “not yet.” The goal of a coach and good program shouldn’t be to see how long you can defy the science, it should be to put you in a position to have longevity, keep your body as healthy as long as possible. It is like saying, “I smoke, but I don’t have cancer.” Well, not yet! You might think this is an extreme example but being in pain is a horrible way to live!

Good workouts and exercise programs aren’t suppose to see you survive, but rather thrive!

Well, in crunches you don’t have that spinal flexion in the low back. That’s pretty fair, in fact, Dr. McGill teaches a specific type of crunch to still train flexion movement in a safer manner. My issue is this, most people train 2-3 days a week if they train at all. Prioritizing the MOST important qualities is key in keeping people healthy so they can train longer. Therefore, if you use such an exercise I have no inherent problem with it, but have to ask, “is it the BEST use of your time?”

Last one, if I don’t do sit-ups and crunches I’ll get super weak in those movements and if these other means of core training are great, then why am I so weak. I think I’ll leave it to Dr. McGill to answer!

“There is confusion between the terms flexion “movement” and flexion “moment”. Flexion movement defines the act of bending the spine forward, flexing the spine. This is the kinematic term. Flexion moment refers to the act of creating flexion moment or torque. This is the kinetic term. This is independent of whether movement occurs. Standing, and pushing a load requires the spine to stiffen with anterior muscle activation, hence flexion moment occurs requiring abdominal muscle strength but not movement.

I was shown a quote recently from a trainer who stated, “I followed McGill and avoided flexion and got so weak I could hardly do a sit-up”. Apart from a terrible misunderstanding and misquote of what we do, this person did not understand the difference between flexion movement and moment. It would appear he avoided moment training. He caused his outcome.”

In other words, many of the core exercises we are showing still train flexion moment without training flexion movement. Understanding the body means we have better ways of building success, strength, and being our healthiest. Like most stories, we have to look at the complete picture and avoid confusing sound bites!

Want to learn more how to use science based core training to enhance how we move, perform, and feel, check out physical therapist, Jessica Bento’s great DVRT Pelvic control program HERE

Check out how we also look to take these foundations to make more dynamic forms of core training.

© 2026 Ultimate Sandbag Training. Site by Jennifer Web Design.