How Trying To FIX Your Pain Makes Your Chronic Pain Worse!

2024-10-31

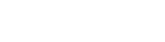

The hedonic treadmill is a psychological concept referring to our tendency to quickly adapt to both positive and negative life changes, returning us to a baseline level of happiness or contentment. This phenomenon is often discussed in the context of happiness and how external gains (like possessions, money, or career achievements) tend to bring only fleeting satisfaction. However, this same mechanism can also apply to the experience of chronic pain, particularly in how it fuels the pursuit of relief and happiness, which can paradoxically intensify pain.

At its core, the hedonic treadmill reflects how the brain is wired to adapt, balancing internal and external conditions to maintain a baseline level of homeostasis. In terms of pain, this adaptation mechanism has a significant impact: while we expect pain to go away after injury, chronic pain involves ongoing discomfort that can profoundly alter a person’s baseline experience. Rather than resetting to a neutral state, the nervous system becomes “stuck” on high alert, so that even minor physical sensations are interpreted as threatening or painful. This neurological state feeds into a cycle where the pursuit of relief from pain can actually heighten pain perception.

One key way the hedonic treadmill fuels chronic pain is through the brain’s tendency to habituate to positive experiences quickly. People experiencing chronic pain often find temporary relief in a new treatment or lifestyle adjustment, only to discover that this relief is short-lived. Much like the way people adapt to happiness-inducing events (like buying a new car or moving to a new city), people in pain can quickly acclimate to the changes they hope will bring relief, making it harder to maintain any positive effects. As a result, chronic pain sufferers may continually seek new treatments, often with diminishing returns. This pursuit can lead to a sense of hopelessness, where people feel “trapped” in their pain, much like being stuck on a treadmill they can’t step off.

Moreover, the pursuit of relief or happiness can create a heightened focus on pain itself, which paradoxically strengthens pain pathways in the brain. Chronic pain alters the brain’s structure and functioning, making it more likely to interpret sensations as painful, even when there is no physical cause. This neuroplasticity—the brain’s ability to reorganize itself based on experience—is a double-edged sword: while it can help us learn new skills, it can also lead the brain to learn chronic pain as a habitual state. Research suggests that the emotional and cognitive focus on pain plays a role in reinforcing these pathways. When individuals strive relentlessly to eliminate their pain, they reinforce the brain’s focus on it, causing it to interpret minor stimuli as painful.

In addition, the hedonic treadmill concept ties directly into the human desire for comfort and happiness, which can create a cycle of avoidance behaviors. Often, people with chronic pain begin to avoid activities they associate with pain, hoping that by minimizing discomfort, they will feel happier and experience less pain. However, this strategy often backfires. Avoidance can lead to muscle weakness, decreased mobility, and reduced tolerance to physical activity, which in turn makes the body more susceptible to pain. This avoidance also extends to social activities and hobbies, leading to isolation and potentially depression, both of which can exacerbate pain through the brain’s negative feedback loops. In attempting to avoid pain, people may inadvertently reinforce it by allowing their bodies and minds to adapt to a more sedentary, isolated, and fragile state.

The relentless pursuit of happiness and pain relief also adds a layer of emotional distress. Chronic pain brings unique challenges, as it is not just the physical sensation of pain but also the emotional toll of dealing with unrelenting discomfort and the perception that life is less fulfilling because of it. This emotional distress further compounds pain through the brain’s limbic system, which is responsible for processing both pain and emotions. Studies have shown that the emotional response to pain—especially frustration, anger, or sadness—can amplify pain perception. When people become overly focused on the pursuit of a pain-free, happy state, they can fall into a cycle where the stress and disappointment of not achieving it intensify their suffering.

What makes this all the more challenging is society’s expectation that we should always pursue happiness and live pain-free lives. Messages in the media and health industry promote a vision of constant health and well-being, which can make those with chronic pain feel inadequate or even guilty for their struggles. This societal pressure reinforces the desire to constantly seek out solutions and relief, leading many to feel disheartened when these solutions fail. In fact, many people with chronic pain experience a sense of “pain fatigue,” where the mental energy spent on seeking relief exhausts them, adding to their suffering and heightening their sense of loss or lack of fulfillment.

If there were simple fixes to the issue of pain people would be RICH, like Tony Stark rich!!!

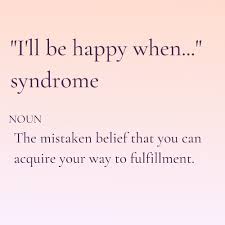

In stepping away from the hedonic treadmill, people with chronic pain can find alternative approaches that foster resilience rather than intensifying the pain cycle. For example, acceptance-based therapies encourage individuals to acknowledge their pain rather than constantly fighting it, which can reduce the mental strain associated with pain. By shifting the goal from being pain-free to functioning well despite the pain, individuals can reclaim some control over their lives and emotions. Mindfulness practices, which train the brain to observe sensations without attaching an emotional response, can also reduce the brain’s sensitivity to pain signals.

In addition, focusing on gradual, sustainable improvements—rather than constant highs or an ideal of perfect happiness—helps individuals to stabilize their expectations. This approach, sometimes called “living well with pain,” encourages people to shift their focus to what they can do rather than what they cannot, building confidence and resilience in the face of pain. Physical activity programs that emphasize gentle, progressive movement rather than intense, pain-focused workouts also show promise. Practices like meditative movement practices, like our MIM programs, can support mental and physical health without triggering the pain-stress feedback loop.

In summary, the hedonic treadmill contributes to chronic pain by perpetuating a cycle of temporary relief, emotional distress, and heightened focus on pain. The desire to eliminate pain entirely often deepens suffering, as the brain reinforces pain pathways and the person may begin to avoid essential activities. By stepping away from the hedonic pursuit of happiness and adopting acceptance-based strategies, individuals can better manage chronic pain, reducing its grip on their lives and finding a new, healthier baseline for comfort and contentment.

What Cory Cripe shows with our MIM movements is NOT just other ways to stretch or move, it is being really intentional in being mindful of feeling all aspects of his body. How his feet engage with the ground, how the movement spirals up his body, the tension he holds in different areas, the quality of the breath he takes, and the judgements he makes about his performance. THIS is what makes MIM so effective while using movement concepts of total body integrated exercises, diagonal and circular patterns, and more.

Check out more with our NEW MIM follow along program HERE as well as other MIM resources HERE 30% off with code “mim30” and we have a VERY limited supply of Mobility Balls left you can check out (but you can do the programs without them) HERE

© 2026 Ultimate Sandbag Training. Site by Jennifer Web Design.