Should You Put Knees Over Toes?

2021-05-19

It has become one of the most INTERESTING discussions that I never saw coming! The now very pro “knees over toes” crowd in fitness and leaking even into the therapy world. Like so many issues, there are many aspects to look at to really understand who is right but more importantly, what do we have to consider to have this discussion.

I believe some of this new idealism of knees SHOULD go over toes is a backlash against the hyper vigilance that people had for many years where they made it sound like if your knees went over your toes your knees would simply explode. When we become overly dogmatic about anything that doesn’t have much evidence to support it, we usually see the pendulum swing really hard the other way. So, I get where some people are coming from, but let’s look at the more important aspects of the conversion about knees over toes.

Can You Have Your Knees Go Over Toes?

Well, like most things the answer is, it depends on the situation of the knees going over the toes and who are we talking about? Before we get into that (which I will explain) let’s be honest why MOST people want to have their knees go over their toes. The majority of people are using elevating the heels during a movement like the squat to help bypass ankle mobility issues that keep themselves or their clients from reaching a good depth of their squat. Elevating the heels gives the artificial dorsiflexion that the ankles would normally want to achieve to allow for a good squat.

While this Marine has his knees go over his toes, you will notice it is from his deep squat and great ankle mobility.

Does this strategy work? It “works” as far as it eliminates the need for dorsiflexion and allows people that have rather poor ankle mobility to squat deeper. In doing so their knees do tend to go over their toes and in a different way than if the feet were flat on the ground. Like anything, if you don’t address the real issue, you are asking for other problems to arise. What would that be in this case?

As a therapist my biggest goal in exercise is to teach skills and build qualities that will make you better at what you do in real life and help you move with as low of a risk of injury as possible. When we don’t address developing ankle mobility we may be able to get you to have a deep squat, but we aren’t making you better outside of the gym.

Studies like the one HERE shows that chronic ankle instability, for example, leads to “Patients with chronic ankle instability demonstrate decreased knee flexion. Decreased knee flexion has shown to be a key risk factor in non-contact knee injuries. In the future, more research needs to be done comparing chronic ankle instability to non-contact knee injury rates.” That lack of knee flexion you may have isn’t from “tight” quads and doesn’t get better from artificially getting your knees over your toes.

Another study HERE showed how restricting ankle dorsiflexion changes what happens at the knee, “Limitations in gastrocnemius/soleus flexibility that restrict ankle dorsiflexion during dynamic tasks have been reported in individuals with patellofemoral pain (PFP) and are theorized to play a role in its development…Altering ankle-dorsiflexion starting position during a double-leg squat resulted in increased knee valgus and MKD, as well as decreased quadriceps activation and increased soleus activation. These changes are similar to those seen in people with PFP.”

Since three is the charm, this study HERE, concluded, ” Conclusion Individuals with lower ankle dorisflexion range of motion exhibited hip and knee kinematics previously associated with several knee disorders, suggesting that this impairment may be involved in the pathogenesis of the same disorders.”

Our first concern should actually not be if the knees are going over the toes, but rather, do we have good ankle dorsiflexion first!!! You can see not having good ankle mobility is going to lead us to more issues and elevating the heels is not going to solve these concerns. That is why I’ve shared some of our DVRT ankle mobility strategies below (you can find more in my DVRT Rx Knees Course HERE)

View this post on Instagram

Instead of trying to elevate my heels, addressing my ankle mobility will lead to success that makes not only for better squats but better movement outside of the gym.

View this post on Instagram

Doesn’t Knees Over Toes Help My Knee Mobility?

One of the most popular reasons I also hear from people wanting to emphasize knees over toes is that they believe it helps knee mobility. Well, if you look at the research that we just covered there is quite a bit of evidence (there are more studies on this as well) that demonstrates that knee flexion is really based upon ankle dorsiflexion. So, we are back at the reality that most of the issues that occur with the knee start at the foot/ankle.

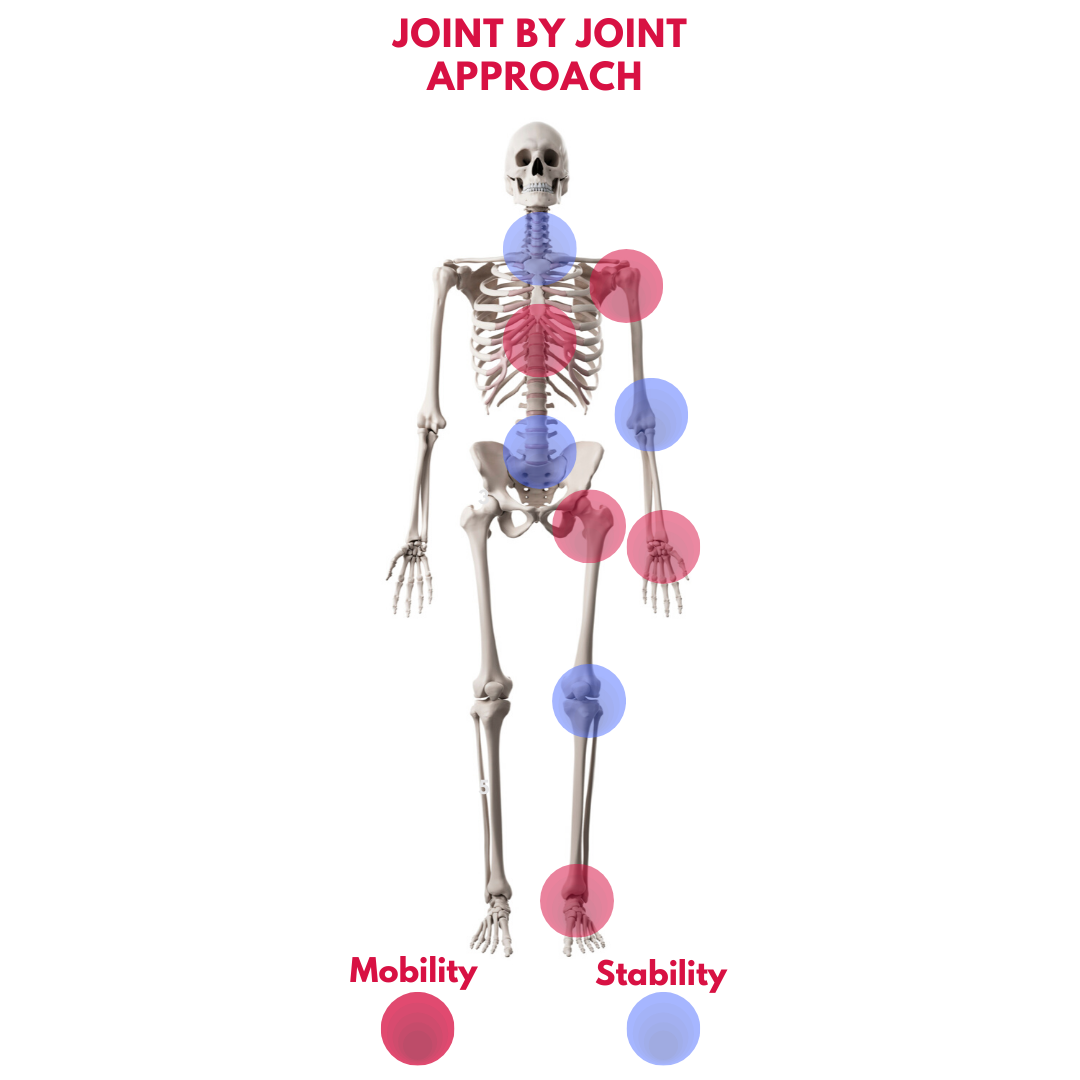

If we look at the classic Joint by Joint approach that we have used many times you can see that if the foot/ankle are off then this will impact both the knees and hips.

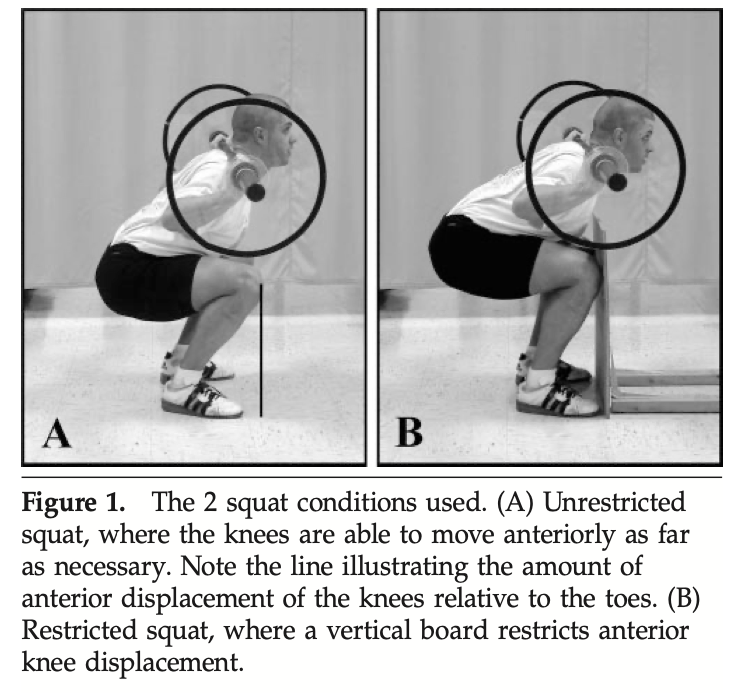

Now, can your knees go over your toes? Well it depends on how you are doing so. For example in a good deep squat your knees are probably going to go over your toes in a rather safe manner as the hamstrings also work synergistically with the other muscles around the knee to help stabilize and support the knee. Our friend, Dr. Brian Schilling, was part of a great study that looked at what happened if we restricted knee movement in a squat versus allowing the natural movement. They found the following…

“Although restricting forward movement of the knees may minimize stress on the knees, it is likely that forces are inappropriately transferred to the hips and low-back region. Thus, appropriate joint loading during this exercise may require the knees to move slightly past the toes.”

If we aren’t altering natural mechanics and the knees go over the toes we are probably fine. However, as the study does state, doing so does increase shear forces upon the knees. While in a squat, for example, this is well tolerated by most, if you have pre-existing knee issues it may cause some issue that you would want to stay away from. As always, if it hurts, don’t do it, but also make sure the quality of your movement is there. As the researchers explain…

“..shear forces have ranged from 30 to 80%…In general, these forces become greater with increasing depth of the squat motion.”

Conveniently, most people online leave out the section after the yellow highlight where it DOES caution people with knee pain/injury with these methods.

It is important to note that deeper squatting does increase shear forces on the knee and while manageable by many it should be considered in what we recommend. When we elevate the heels this amplifies the shear force acting upon the knees (the type of force we should be more concerned with than compression) as does any time we are deliberately trying to push the knees over the toes (even with good ankle mobility we do increase shear force).

The last point I always hear as well is that we need to train in these “extreme” (usually the verbiage used by others) ranges of motion to protect the body. While at first glance this makes sense, going deeper we learn that it isn’t accurate. Dr. Travis Pollen explains why really well…

“There are a few reasons to question the notion that closing the active ROM/passive ROM gap is paramount for injury prevention. The first is that while many acute, sudden-onset injuries do tend to happen in end ranges, they are generally the result of high forces applied at high velocities – such as an impact, a fall, or some other type of traumatic accident. By contrast, the forces involved in most end-range training practices are lower in magnitude and velocity and are therefore unlikely to be protective against most acute, sudden-onset injuries….End-range training most commonly involves taking a joint into its end range and performing isometric contractions in that position. Isometric contractions by definition involve no movement and therefore no speed. Although we can work to “ramp up” our contractions to feel quite effortful while we’re doing them, this type of strength work is simply no match for the higher, faster forces involved in acute, sudden-onset injuries….The strength and neurological control that would really have the potential to prevent acute injuries is the strength and control of a joint before it reaches end range – i.e. more toward its mid-range. As we mentioned, due to the length-tension relationship, our muscles have the most active force production available toward their mid ranges, not their end ranges. So that’s the range in which we’d have the most likelihood of “catching” ourselves in the midst of a potential injurious accident, both from a strength and neurological control perspective. In other words, suppose we lack strength and control in our mid-range joint angles. No amount of end-range strength will likely be able to stop the momentum that’s already developed in an accident-type situation by our inability to control our movement well before we reach that end-range position.”

In other words, we want to have strength in ranges that we can prevent these “extremes” from occurring because the chances of us being able to react and have enough power to absorb these forces is VERY low even with the best of end range training. Instead, let’s teach good movement and we can let the body do what it naturally is designed to act. For example, when we teach squatting we can use tools in very specific ways to teach proper core stability that helps us gain better hip and knee action like those below.

We can and probably should continue this discussion and you are free to write in with questions/comments. My hope is that you have a better understanding of the questions we should be asking and the issues we should be looking to solve. Often there is so much information out there it is tough to tell which way is up. I truly do hope that this blog at least starts you in the right direction!

WE BREAK DOWN THESE STRATEGIES AND SO MUCH MORE IN OUR DVRT RX KNEE PROGRAMS THAT ARE 35% OFF HERE WITH CODE “KNEEPAIN” HERE

View this post on Instagram

Cory Cripe does a great job of breaking down DVRT squat progressions that make our movement great and knees healthy.

© 2026 Ultimate Sandbag Training. Site by Jennifer Web Design.