Why Shoulder Pain Isn’t Just a Shoulder Problem

2026-01-27

Jessica Bento, Physical Therapist

Shoulder and thoracic discomfort are two of the most common complaints seen in fitness, rehabilitation, and everyday life. Long hours of sitting, screen use, repetitive tasks, and stress-driven postures gradually limit thoracic mobility and alter shoulder mechanics. When the mid-back stops moving well, the shoulders are forced to compensate, often leading to pain, stiffness, and reduced performance. A Myofascial Integrated Movement (MIM) approach addresses this problem at its root by restoring movement quality through the fascial system rather than isolating individual muscles.

The thoracic spine is designed to rotate, extend, and flex smoothly. Research shows that reduced thoracic mobility is strongly associated with shoulder pain and dysfunction (Strunce et al., 2009; Kebaetse et al., 1999). When thoracic motion is limited, the shoulder joint must move excessively to achieve the same range of motion, increasing joint stress. This compensation pattern is a major contributor to impingement syndromes, rotator cuff irritation, and chronic shoulder tension.

Traditional exercise approaches often focus on strengthening isolated shoulder muscles or stretching single tight structures. While these can be helpful, they do not fully address the interconnected nature of human movement. Fascia connects every muscle, joint, and organ into a continuous system of tension and force transmission. Schleip et al. (2012) describe fascia as a sensory-rich tissue capable of adapting its stiffness and organization based on movement, load, and hydration. This means that improving movement quality and variability can directly influence tissue health, mobility, and comfort.

View this post on Instagram

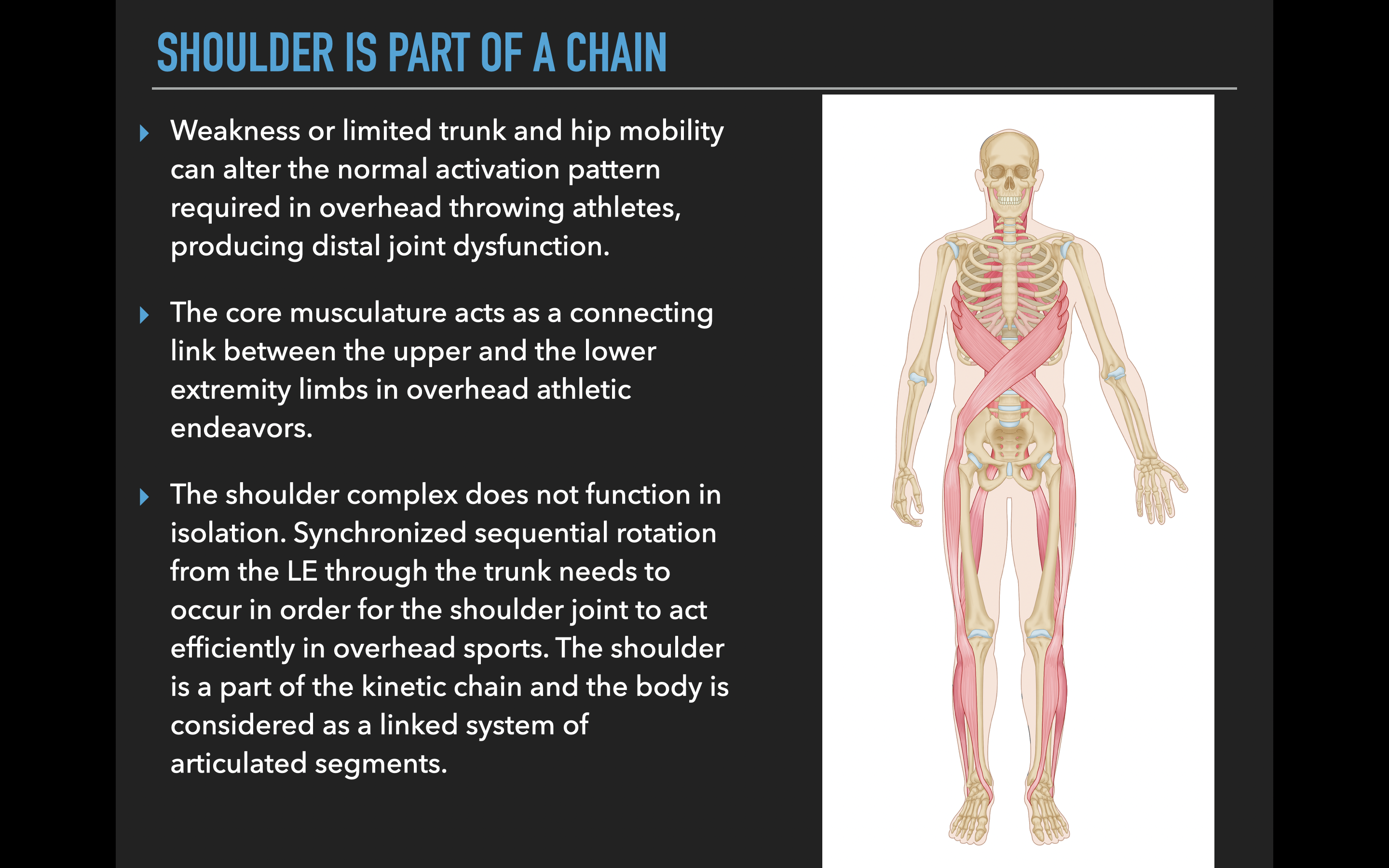

Myofascial Integrated Movement works by re-establishing efficient load transfer across the body through large, coordinated movement patterns rather than isolated muscle actions. The shoulder does not function independently; it relies on proper thoracic motion, rib cage expansion, pelvic positioning, and even foot-ground interaction. By training the system as a whole, MIM helps normalize the movement environment in which the shoulder operates.

One of the most important myofascial relationships affecting shoulder function is the connection between the thoracic spine, ribs, scapula, and arm. Myers’ “Anatomy Trains” model describes several fascial lines that influence shoulder mechanics, including the superficial front line, superficial back line, spiral line, and functional lines (Myers, 2014). Restrictions in any of these pathways can alter scapular positioning and glenohumeral joint mechanics. MIM uses integrated movements that naturally load and unload these fascial chains, promoting elasticity, hydration, and sliding between tissue layers.

Thoracic mobility improves when movement is dynamic, three-dimensional, and breath-supported. Research shows that active mobility training produces greater and longer-lasting improvements in joint range of motion compared to passive stretching alone (Behm et al., 2016). MIM emphasizes rotational, diagonal, and spiral-based movement patterns that restore thoracic rotation and extension while simultaneously coordinating shoulder motion. This creates mobility that is usable, not just temporary flexibility.

Breathing is another essential component. The diaphragm is deeply connected to the thoracic spine and rib cage via fascial attachments. Poor breathing mechanics limit rib mobility and contribute to excessive tension in the neck and shoulders. Kocjan et al. (2017) demonstrated that respiratory muscle function is strongly linked to trunk stability and posture. MIM integrates breathing with movement, allowing the rib cage to expand and rotate naturally, which reduces compressive stress in the shoulder complex and improves thoracic freedom.

From a neurological standpoint, movement quality is influenced by sensory input from fascia. Fascia contains mechanoreceptors that inform the nervous system about body position, tension, and safety (Schleip et al., 2012). Slow, controlled, integrated movement improves proprioception and reduces protective muscle guarding. Many people with shoulder discomfort are not weak; they are over-protective. MIM helps reintroduce safe movement variability, allowing the nervous system to release unnecessary tension.

Another benefit of MIM is improved scapular mechanics. Healthy shoulder movement requires coordinated motion between the humerus and scapula, known as scapulohumeral rhythm. Altered thoracic posture disrupts this rhythm, often leading to excessive upper trapezius activity and reduced lower trapezius and serratus anterior engagement. Studies show that restoring thoracic posture and mobility improves scapular kinematics and reduces shoulder pain (Kebaetse et al., 1999; Strunce et al., 2009). Because MIM integrates trunk and arm movement together, it naturally retrains this coordination without cueing individual muscles.

The fascial system also responds positively to low-load, multi-directional movement. Langevin et al. (2011) showed that fascia remodels in response to mechanical stress, hydration, and movement variability. When people repeat the same exercises in the same planes of motion, tissue adaptability decreases. MIM encourages movement diversity, which supports tissue elasticity and resilience. This is especially valuable for individuals with chronic stiffness or long-standing discomfort.

Pain science further supports this approach. Persistent pain is often less about tissue damage and more about altered movement patterns and nervous system sensitivity (Moseley & Butler, 2015). By improving movement confidence, fluidity, and coordination, MIM helps shift the body from a threat-based pattern to a safety-based one. Clients frequently report that their shoulders feel “lighter,” “freer,” or “less guarded,” even before large strength changes occur.

For adults over 40, these effects become even more important. Aging is associated with reduced tissue hydration, decreased movement variability, and increased joint stiffness. However, research shows that connective tissue remains adaptable throughout the lifespan when exposed to appropriate mechanical input (Schleip et al., 2012). MIM provides that input in a joint-friendly, nervous-system-supportive way, making it ideal for restoring shoulder and thoracic mobility without aggressive loading.

In practical terms, a Myofascial Integrated Movement program helps by:

-

Reconnecting shoulder motion to thoracic rotation and rib mobility

-

Improving breathing mechanics and reducing upper-body tension

-

Restoring fascial elasticity through spiral and diagonal movement patterns

-

Enhancing neuromuscular coordination and proprioception

-

Reducing protective guarding that contributes to chronic discomfort

Rather than forcing flexibility or isolating strength, MIM builds movement capacity from the inside out. When the thoracic spine moves better, the shoulder no longer has to compensate. When fascia becomes hydrated and responsive, stiffness decreases naturally. When the nervous system feels safe, tension releases.

This is why Myofascial Integrated Movement is so effective for shoulder and thoracic discomfort. It does not chase symptoms; it restores the environment in which healthy movement emerges. By respecting the body’s interconnected design, MIM supports long-term mobility, resilience, and comfort.

Don’t miss the chance to save on ALL our MIM programs including our NEW MIM Intensive Coaching & Strength Programs along with our MIM Shoulder Program HERE with code “mim30”

References

Behm, D. G., et al. (2016). Acute effects of muscle stretching on physical performance, range of motion, and injury incidence in healthy active individuals. Applied Physiology, Nutrition, and Metabolism, 41(1), 1–11.

Kebaetse, M., McClure, P., & Pratt, N. A. (1999). Thoracic position effect on shoulder range of motion, strength, and three-dimensional scapular kinematics. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 80(8), 945–950.

Langevin, H. M., et al. (2011). Connective tissue fibroblast response to stretching. Journal of Cellular Physiology, 226(3), 784–792.

Myers, T. (2014). Anatomy Trains: Myofascial Meridians for Manual and Movement Therapists. Elsevier.

Moseley, G. L., & Butler, D. S. (2015). Fifteen years of explaining pain: The past, present, and future. Journal of Pain, 16(9), 807–813.

Schleip, R., Findley, T. W., Chaitow, L., & Huijing, P. (2012). Fascia: The Tensional Network of the Human Body. Elsevier.

Strunce, J. B., et al. (2009). The immediate effects of thoracic spine and rib manipulation on subjects with primary complaints of shoulder pain. Journal of Manual & Manipulative Therapy, 17(4), 230–236.

Kocjan, J., et al. (2017). Respiratory muscle strength and its relation to postural stability. Journal of Physical Therapy Science, 29(3), 456–461.

© 2026 Ultimate Sandbag Training. Site by Jennifer Web Design.